I think everyone already knows my opinions about MERGE and why I stay away from it. But here's another (anti-)pattern I see all over the place when people want to perform an upsert (update a row if it exists and insert it if it doesn't):

IF EXISTS (SELECT 1 FROM dbo.t WHERE [key] = @key)

BEGIN

UPDATE dbo.t SET val = @val WHERE [key] = @key;

END

ELSE

BEGIN

INSERT dbo.t([key], val) VALUES(@key, @val);

END

This looks like a pretty logical flow that reflects how we think about this in real life:

- Does a row already exist for this key?

- YES: OK, update that row.

- NO: OK, then add it.

But this is wasteful.

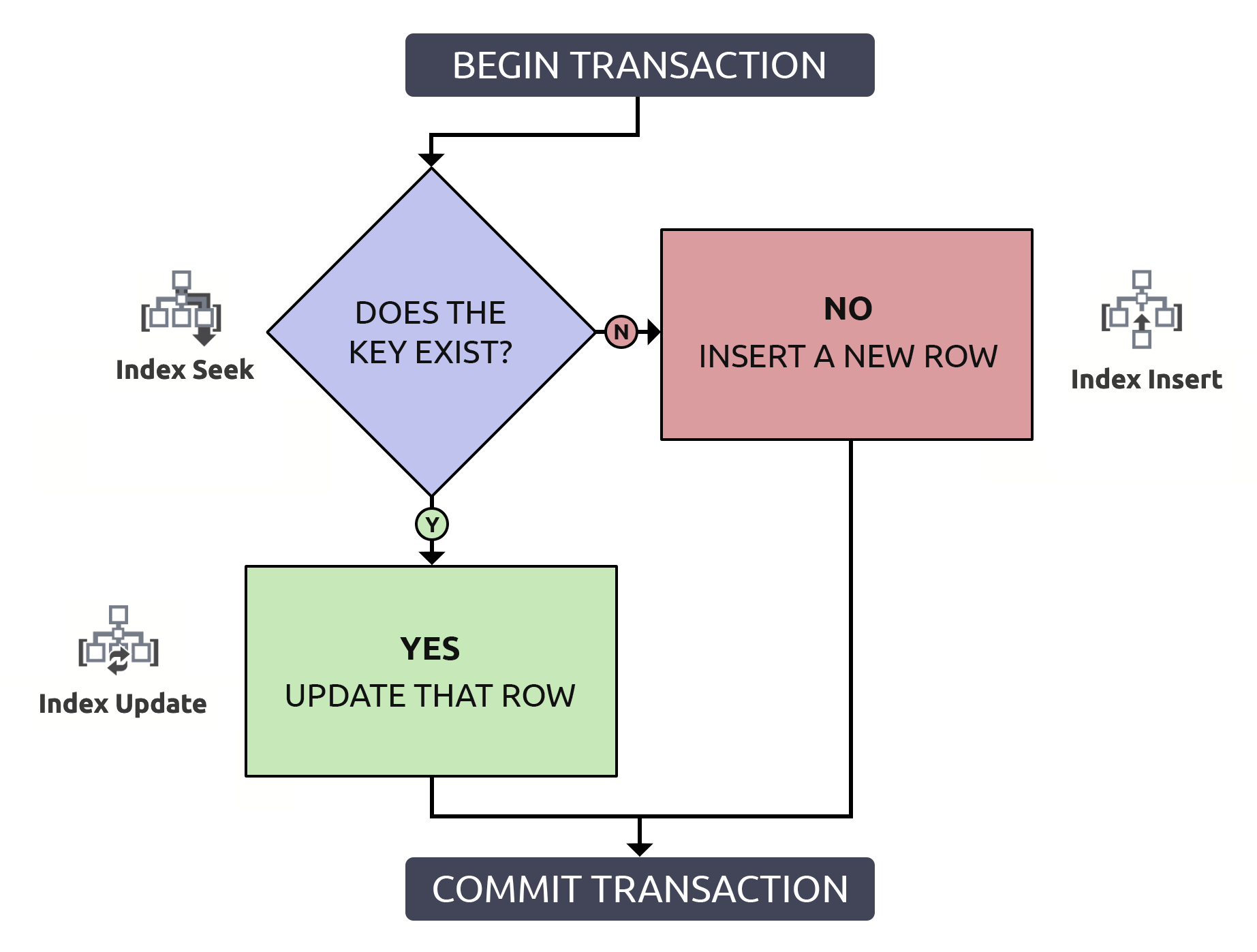

Locating the row to confirm it exists, only to have to locate it again in order to update it, is doing twice the work for nothing. Even if the key is indexed (which I hope is always the case). If I put this logic into a flow chart and associate, at each step, the type of operation that would have to happen within the database, I'd have this:

Notice that all paths will incur two index operations.

Notice that all paths will incur two index operations.

More importantly, performance aside, unless you both use an explicit transaction and elevate isolation level, multiple things could go wrong when the row doesn't already exist:

- If the key exists and two sessions try to update simultaneously, they'll both update successfully (one will "win"; the "loser" will follow with the change that sticks, leading to a "lost update"). This isn't a problem on its own, and is how we should expect a system with concurrency to work. Paul White talks about the internal mechanics in greater detail here, and Martin Smith talks about some other nuances here.

- If the key doesn't exist, but both sessions pass the existence check the same way, anything could happen when they both try to insert:

- deadlock because of incompatible locks;

- raise key violation errors that shouldn't have happened; or,

- insert duplicate key values if that column isn't properly constrained.

That last one is the worst, IMHO, because it's the one that potentially corrupts data. Deadlocks and exceptions can be handled easily with things like error handling, XACT_ABORT, and retry logic, depending on how frequently you expect collisions. But if you are lulled into a sense of security that the IF EXISTS check protects you from duplicates (or key violations), that is a surprise waiting to happen. If you expect a column to act like a key, make it official and add a constraint.

"Many people are saying…"

Dan Guzman talked about race conditions more than a decade ago in Conditional INSERT/UPDATE Race Condition and later in "UPSERT" Race Condition With MERGE.

Michael Swart has also treated this subject multiple times:

- Mythbusting: Concurrent Update/Insert Solutions – where he acknowledged that leaving the initial logic in place and only elevating the isolation level just changed key violations to deadlocks;

- Be Careful with the Merge Statement – where he checked his enthusiasm about

MERGE; and, - What To Avoid If You Want To Use MERGE – where he confirmed once again that there are still plenty of valid reasons to continue avoiding

MERGE.

Make sure you read all the comments on all three posts, too.

The Solution

I've fixed many deadlocks in my career by simply adjusting to the following pattern (ditch the redundant check, wrap the sequence in a transaction, and protect the first table access with appropriate locking):

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

UPDATE dbo.t WITH (UPDLOCK, SERIALIZABLE) SET val = @val WHERE [key] = @key;

IF @@ROWCOUNT = 0

BEGIN

INSERT dbo.t([key], val) VALUES(@key, @val);

END

COMMIT TRANSACTION;

Why do we need two hints? Isn't UPDLOCK enough?

UPDLOCKis used to protect against conversion deadlocks at the statement level (let another session wait instead of encouraging a victim to retry).SERIALIZABLEis used to protect against changes to the underlying data throughout the transaction (ensure a row that doesn't exist continues to not exist).

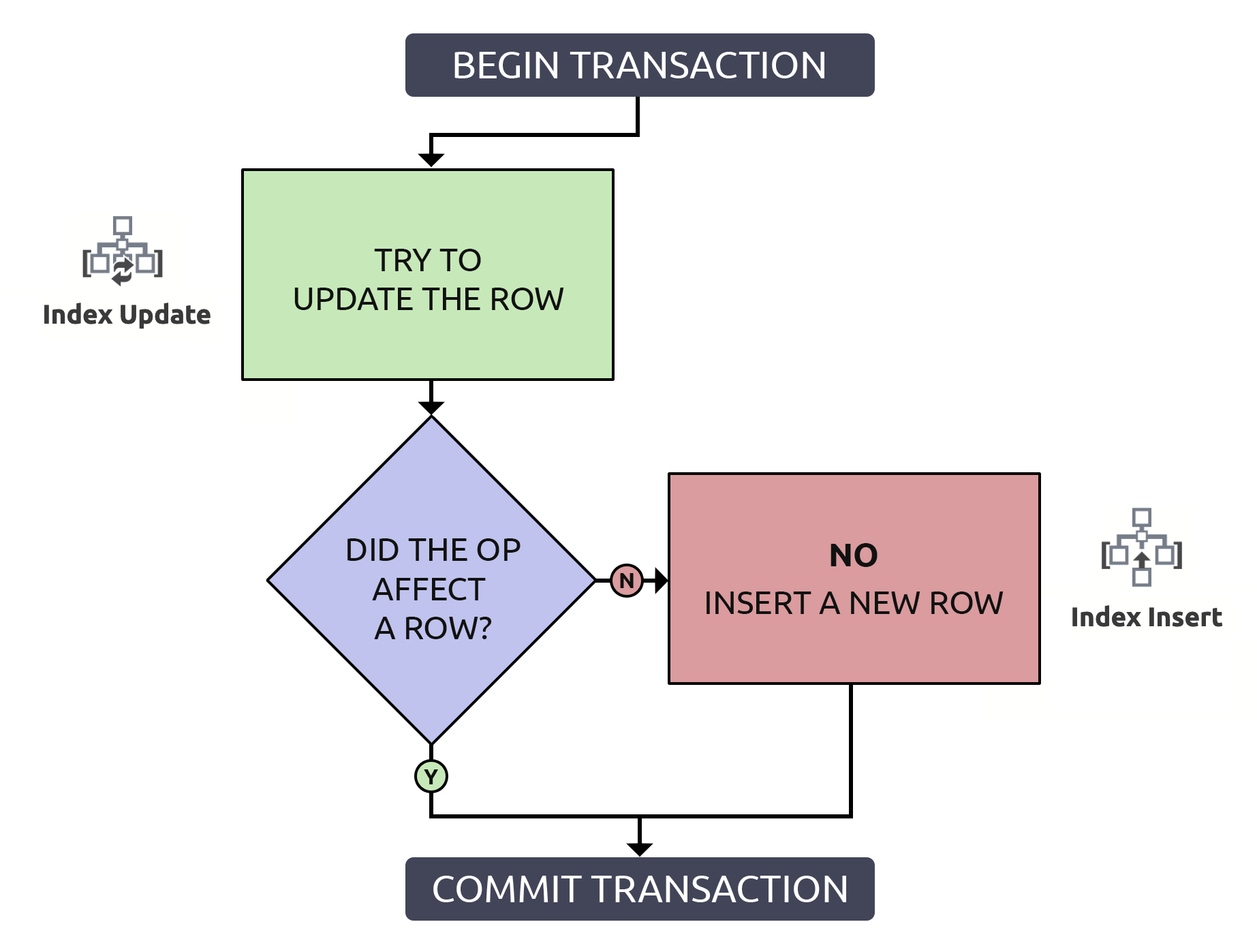

It's a little more code, but it's 1000% safer, and even in the worst case (the row does not already exist), it performs the same as the anti-pattern. In the best case, if you are updating a row that already exists, it will be more efficient to only locate that row once. Combining this logic with the high-level operations that would have to happen in the database, it is slightly simpler:

In this case, one path only incurs a single index operation.

In this case, one path only incurs a single index operation.

But again, performance aside:

- If the key exists and two sessions try to update it at the same time, they'll both take turns and update the row successfully, like before.

- If the key doesn't exist, one session will "win" and insert the row. The other will have to wait until the locks are released to even check for existence, and be forced to update.

In both cases, the writer who won the race loses their data to anything the "loser" updated after them.

Note that overall throughput on a highly concurrent system might suffer, but that is a trade-off you should be willing to make. That you're getting lots of deadlock victims or key violation errors, but they're happening quickly, is not a good performance metric. Some folks would love to see all blocking removed from all scenarios, but some of that is blocking you absolutely want for data integrity.

But what if an update is less likely?

It is clear that the above solution optimizes for updates, and assumes that a key you're trying to write to will already exist in the table as least as often as it doesn't. If you would rather optimize for inserts, knowing or guessing that inserts will be more likely than updates, you can flip the logic around and still have a safe upsert operation:

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

INSERT dbo.t([key], val)

SELECT @key, @val

WHERE NOT EXISTS

(

SELECT 1 FROM dbo.t WITH (UPDLOCK, SERIALIZABLE)

WHERE [key] = @key

);

IF @@ROWCOUNT = 0

BEGIN

UPDATE dbo.t SET val = @val WHERE [key] = @key;

END

COMMIT TRANSACTION;

There's also the "just do it" approach, where you blindly insert and let collisions raise exceptions to the caller:

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

BEGIN TRY

INSERT dbo.t([key], val) VALUES(@key, @val);

END TRY

BEGIN CATCH

UPDATE dbo.t SET val = @val WHERE [key] = @key;

END CATCH

COMMIT TRANSACTION;

The cost of those exceptions will often outweigh the cost of checking first; you'll have to try it with a roughly accurate guess of hit/miss rate. I wrote about this here and here.

What about upserting multiple rows?

The above deals with singleton insert/update decisions, but Justin Pealing asked what to do when you are processing multiple rows without knowing which of them already exist?

Assuming you are sending a set of rows in using something like a table-valued parameter, you would update using a join, and then insert using NOT EXISTS, but the pattern would still be equivalent to the first approach above:

CREATE PROCEDURE dbo.UpsertTheThings

@tvp dbo.TableType READONLY

AS

BEGIN

SET NOCOUNT ON;

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

UPDATE t WITH (UPDLOCK, SERIALIZABLE)

SET val = tvp.val

FROM dbo.t AS t

INNER JOIN @tvp AS tvp

ON t.[key] = tvp.[key];

INSERT dbo.t([key], val)

SELECT [key], val FROM @tvp AS tvp

WHERE NOT EXISTS (SELECT 1 FROM dbo.t WHERE [key] = tvp.[key]);

COMMIT TRANSACTION;

END

If you're getting multiple rows together in some other way than a TVP (XML, comma-separated list, voodoo), put them into a table form first, and join to whatever that is. Be careful not to optimize for inserts first in this scenario, otherwise you'll potentially update some rows twice.

Conclusion

These upsert patterns are superior to the ones I see all too often, and I hope you start using them. I will point to this post every time I spot the IF EXISTS pattern in the wild. And, hey, another shoutout to Paul White (sql.kiwi | @SQK_Kiwi), because he is so excellent at making hard concepts easy to understand and, in turn, explain.

And if you feel you have to use MERGE, please don't @ me; either you have a good reason (maybe you need some obscure MERGE-only functionality), or you didn't take the above links seriously.

Blah blah blah. Been hearing this crap for 20 years…most apps just are not concurrent like this. This code makes sense to people.

I learned UPDLOCK and SERIALIZABLE so, thanks for that. But I have a question:

at the upserting multiple rows scenario, shouldn't be UPDLOCK, SERIALIZABLE hints used when inserting?

If I understand correctly; without it, transaction won't be collision and/or deadlock proof. Or does transaction prevent releasing lock from previous update statement?

Sorry, I missed a key word (no pun intended) in your comment initially; I thought you were talking about the "single-row, insert first" approach.

I'd have to think about any possible ways this could fail as written, and I think the transaction wrapper protects the insert case without the hints (unless you also have concurrent sessions that process in the reverse order, inserts first; but you should never do this with multiple rows, as I explained in the post). I'm not opposed to adding them, but maybe you can help me nail down a scenario that actually could yield a deadlock/race (other than blocking and lost updates, which are expected facts of a concurrent life). I tried several ways to make it fail by injecting artificial delays in between the two statements for two competing sessions, but couldn't – and didn't see any material difference between applying the hint and not, except that without the hint there are 1 or 2 additional key RangeX-X locks. I suppose if you wanted to be ultra conservative you could just wrap the whole thing in serializable; though, technically, a batch that only updates shouldn't have to block a batch that only inserts, and vice-versa.

Without UPDLOCK/SERIALIZABLE: empty table, mostly inserts | mostly updates

With UPDLOCK/SERIALIZABLE: empty table, mostly inserts | mostly updates

I'll do some more testing when I have a chance, with data coming from a permanent source instead of a TVP (which lets me control the transaction a little better than all these sync/waitfor gymnastics).

Sure, but like MERGE, if that syntax existed in SQL Server, I expect you would still need the right locking/isolation semantics because that is still fundamentally two distinct operations (even though the syntax makes it seem like one). This may work differently on other platforms, but the point of this post was not to seek out how other database platforms handle this type of operation.

I believe that's automatic in mysql/mariadb:

"INSERT … ON DUPLICATE KEY UPDATE differs from a simple INSERT in that an exclusive lock rather than a shared lock is placed on the row to be updated when a duplicate-key error occurs. An exclusive index-record lock is taken for a duplicate primary key value. An exclusive next-key lock is taken for a duplicate unique key value."

— direct from https://dev.mysql.com/doc/refman/8.0/en/innodb-locks-set.html