A common element used in database design is the constraint. Constraints come in a variety of flavors (e.g. default, unique) and enforce the integrity of the column(s) on which they exist. When implemented well, constraints are a powerful component in the design of a database because they prevent data that doesn’t meet set criteria from getting into a database. However, constraints can be violated using commands such as WITH NOCHECK and IGNORE_CONSTRAINTS. In addition, when using the REPAIR_ALLOW_DATA_LOSS option with any DBCC CHECK command to repair database corruption, constraints are not considered.

Consequently, it is possible to have invalid data in the database – either data that doesn’t adhere to a constraint, or data that no longer maintains the expected primary-foreign key relationship. SQL Server includes the DBCC CHECKCONSTRAINTS statement to find data that violates constraints. After any repair option executes, run DBCC CHECKCONSTRAINTS for the entire database to ensure there are no issues, and there may be times when it’s appropriate to run CHECKCONSTRAINTS for a select constraint or a table. Maintaining data integrity is critical, and while it’s not typical to run DBCC CHECKCONSTRAINTS on a scheduled basis to find invalid data, when you do need to run it, it’s a good idea to understand the performance impact it may create.

DBCC CHECKCONSTRAINTS can execute for a single constraint, a table, or the entire database. Like other check commands, it can take substantial time to complete and will consume system resources, particularly for larger databases. Unlike other check commands, CHECKCONSTRAINTS does not use a database snapshot.

With Extended Events we can examine resource usage when we execute DBCC CHECKCONSTRAINTS for the table. To better show the impact, I ran the Create Enlarged AdventureWorks Tables.sql script from Jonathan Kehayias (blog | @SQLPoolBoy) to create larger tables. Jonathan’s script only creates the indexes for the tables, so the statements below are necessary to add a few selected constraints:

USE [AdventureWorks2012];

GO

ALTER TABLE [Sales].[SalesOrderDetailEnlarged]

WITH CHECK ADD CONSTRAINT [FK_SalesOrderDetailEnlarged_SalesOrderHeaderEnlarged_SalesOrderID]

FOREIGN KEY([SalesOrderID])

REFERENCES [Sales].[SalesOrderHeaderEnlarged] ([SalesOrderID])

ON DELETE CASCADE;

GO

ALTER TABLE [Sales].[SalesOrderDetailEnlarged]

WITH CHECK ADD CONSTRAINT [CK_SalesOrderDetailEnlarged_OrderQty]

CHECK (([OrderQty]>(0)))

GO

ALTER TABLE [Sales].[SalesOrderDetailEnlarged]

WITH CHECK ADD CONSTRAINT [CK_SalesOrderDetailEnlarged_UnitPrice]

CHECK (([UnitPrice]>=(0.00)));

GO

ALTER TABLE [Sales].[SalesOrderHeaderEnlarged]

WITH CHECK ADD CONSTRAINT [CK_SalesOrderHeaderEnlarged_DueDate]

CHECK (([DueDate]>=[OrderDate]))

GO

ALTER TABLE [Sales].[SalesOrderHeaderEnlarged]

WITH CHECK ADD CONSTRAINT [CK_SalesOrderHeaderEnlarged_Freight]

CHECK (([Freight]>=(0.00)))

GO

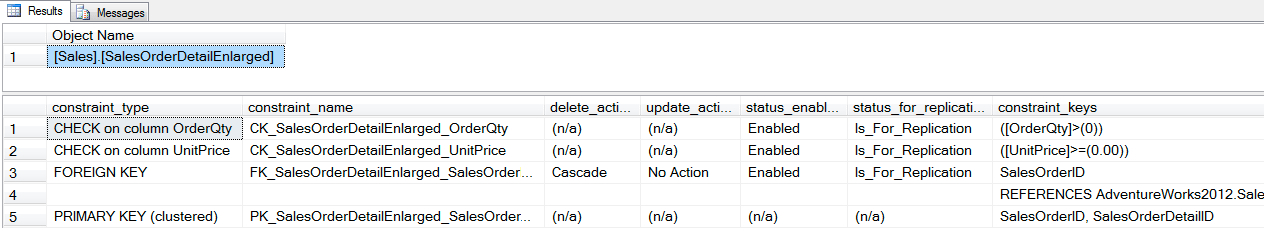

We can verify what constraints exist using sp_helpconstraint:

EXEC sp_helpconstraint '[Sales].[SalesOrderDetailEnlarged]';

GO

Once the constraints exist, we can compare the resource usage for DBCC CHECKCONSTRAINTS for a single constraint, a table, and the entire database using Extended Events. First we’ll create a session that simply captures sp_statement_completed events, includes the sql_text action, and sends the output to the ring_buffer:

CREATE EVENT SESSION [Constraint_Performance] ON SERVER

ADD EVENT sqlserver.sp_statement_completed

(

ACTION(sqlserver.database_id,sqlserver.sql_text)

)

ADD TARGET package0.ring_buffer

(

SET max_events_limit=(5000)

)

WITH

(

MAX_MEMORY=32768 KB, EVENT_RETENTION_MODE=ALLOW_SINGLE_EVENT_LOSS,

MAX_DISPATCH_LATENCY=30 SECONDS, MAX_EVENT_SIZE=0 KB,

MEMORY_PARTITION_MODE=NONE, TRACK_CAUSALITY=OFF, STARTUP_STATE=OFF

);

GO

Next we’ll start the session and run each of the DBCC CHECKCONSTRAINT commands, then output the ring buffer to a temp table to manipulate. Note that DBCC DROPCLEANBUFFERS executes before each check so that each starts from cold cache, keeping a level testing field.

ALTER EVENT SESSION [Constraint_Performance]

ON SERVER

STATE=START;

GO

USE [AdventureWorks2012];

GO

DBCC DROPCLEANBUFFERS;

GO

DBCC CHECKCONSTRAINTS ('[Sales].[CK_SalesOrderDetailEnlarged_OrderQty]') WITH NO_INFOMSGS;

GO

DBCC DROPCLEANBUFFERS;

GO

DBCC CHECKCONSTRAINTS ('[Sales].[FK_SalesOrderDetailEnlarged_SalesOrderHeaderEnlarged_SalesOrderID]') WITH NO_INFOMSGS;

GO

DBCC DROPCLEANBUFFERS;

GO

DBCC CHECKCONSTRAINTS ('[Sales].[SalesOrderDetailEnlarged]') WITH NO_INFOMSGS;

GO

DBCC DROPCLEANBUFFERS;

GO

DBCC CHECKCONSTRAINTS WITH ALL_CONSTRAINTS, NO_INFOMSGS;

GO

DECLARE @target_data XML;

SELECT @target_data = CAST(target_data AS XML)

FROM sys.dm_xe_sessions AS s

INNER JOIN sys.dm_xe_session_targets AS t

ON t.event_session_address = s.[address]

WHERE s.name = N'Constraint_Performance'

AND t.target_name = N'ring_buffer';

SELECT

n.value('(@name)[1]', 'varchar(50)') AS event_name,

DATEADD(HOUR ,DATEDIFF(HOUR, SYSUTCDATETIME(), SYSDATETIME()),n.value('(@timestamp)[1]', 'datetime2')) AS [timestamp],

n.value('(data[@name="duration"]/value)[1]', 'bigint') AS duration,

n.value('(data[@name="physical_reads"]/value)[1]', 'bigint') AS physical_reads,

n.value('(data[@name="logical_reads"]/value)[1]', 'bigint') AS logical_reads,

n.value('(action[@name="sql_text"]/value)[1]', 'varchar(max)') AS sql_text,

n.value('(data[@name="statement"]/value)[1]', 'varchar(max)') AS [statement]

INTO #EventData

FROM @target_data.nodes('RingBufferTarget/event[@name=''sp_statement_completed'']') AS q(n);

GO

ALTER EVENT SESSION [Constraint_Performance]

ON SERVER

STATE=STOP;

GO

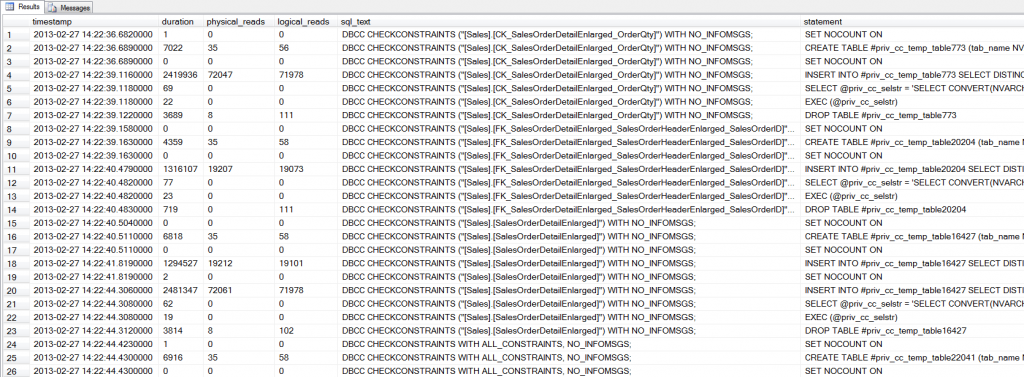

Parsing the ring_buffer into a temp table may take some additional time (about 20 seconds on my machine), but repeated querying of the data is faster from a temp table than via the ring_buffer. If we look at the output we see there are several statements executed for each DBCC CHECKCONSTRAINTS:

SELECT *

FROM #EventData

WHERE [sql_text] LIKE 'DBCC%';

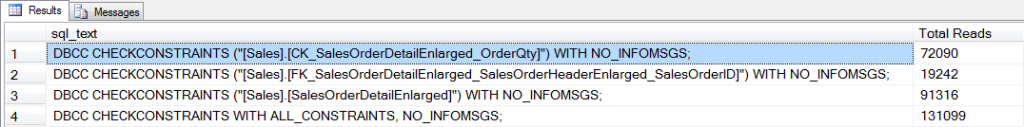

Using Extended Events to dig into the inner workings of CHECKCONSTRAINTS is an interesting task, but what we’re really interested here is resource consumption – specifically I/O. We can aggregate the physical_reads for each check command to compare the I/O:

SELECT [sql_text], SUM([physical_reads]) AS [Total Reads]

FROM #EventData

WHERE [sql_text] LIKE 'DBCC%'

GROUP BY [sql_text];

In order to check a constraint, SQL Server has to read through the data to find any rows that might violate the constraint. The definition of the CK_SalesOrderDetailEnlarged_OrderQty constraint is [OrderQty] > 0. The foreign key constraint, FK_SalesOrderDetailEnlarged_SalesOrderHeaderEnlarged_SalesOrderID, establishes a relationship on SalesOrderID between the [Sales].[SalesOrderHeaderEnlarged] and [Sales].[SalesOrderDetailEnlarged] tables. Intuitively it might seem as though checking the foreign key constraint would require more I/O, as SQL Server must read data from two tables. However, [SalesOrderID] exists in the leaf level of the IX_SalesOrderHeaderEnlarged_SalesPersonID nonclustered index on the [Sales].[SalesOrderHeaderEnlarged] table, and in the IX_SalesOrderDetailEnlarged_ProductID index on the [Sales].[SalesOrderDetailEnlarged] table. As such, SQL Server scans those two indexes to compare the [SalesOrderID] values between the two tables. This requires just over 19,000 reads. In the case of the CK_SalesOrderDetailEnlarged_OrderQty constraint, the [OrderQty] column is not included in any index, so a full scan of the clustered index occurs, which requires over 72,000 reads.

When all the constraints for a table are checked, the I/O requirements are higher than if a single constraint is checked, and they increase again when the entire database is checked. In the example above, the [Sales].[SalesOrderHeaderEnlarged] and [Sales].[SalesOrderDetailEnlarged] tables are disproportionally larger than other tables in the database. This is not uncommon in real-world scenarios; very often databases have several large tables which comprise a large portion of the database. When running CHECKCONSTRAINTS for these tables, be aware of the potential resource consumption required for the check. Run checks during off hours when possible to minimize user impact. In the event that checks must be running during normal business hours, understanding what constraints exist, and what indexes exist to support validation, can help gauge the effect of the check. You can execute checks in a test or development environment first to understand the performance impact, but variations may then exist based on hardware, comparable data, etc. And finally, remember that any time you run a check command that includes the REPAIR_ALLOW_DATA_LOSS option, follow the repair with DBCC CHECKCONSTRAINTS. Database repair does not take any constraints into account as corruption is fixed, so in addition to potentially losing data, you may end up with data that violates one or more constraints in your database.

When you list the reads, I'm curious. What is the total number of pages for these tables once they're expanded? Is the reads 100% of the pages? 200% (scanning both sides of the constraint)?

Can you compare this in time/resources to the work done by checkdb? I'm looking to gauge what this means for checks after some DR or recovery situation.

Also, thanks for this. CHECK CONSTRAINT was one of those things unconsciously incompetent areas ("I didn't know I didn't know") for me. Never had a reason to run this.

Steve-

If I run:

SET STATISTICS IO ON;

USE [AdventureWorks2012];

GO

SELECT [OrderQty]

FROM [Sales].[SalesOrderDetailEnlarged];

GO

When I look at the output from statistics IO, I see 71748 logical reads. If I run:

SELECT OBJECT_NAME([ps].[object_id]), [ps].[index_id], [si].[name], [ps].[used_page_count]

FROM [sys].[dm_db_partition_stats] [ps]

JOIN [sys].[indexes] [si] ON [ps].[object_id] = [si].[object_id] AND [ps].[index_id] = [si].[index_id]

WHERE [si].[object_id] = OBJECT_ID(N'Sales.SalesOrderDetailEnlarged')

OR [si].[object_id] = OBJECT_ID(N'Sales.SalesOrderHeaderEnlarged');

SalesOrderDetailEnlarged and index_id = 1 (the clustered index) I get 71752 used pages – so the check for the CK_SalesOrderDetailEnlarged_OrderQty matches.

Now, for the foreign key, I said it was using two nonclustered indexes for the reads – and I know this because I captured the execution plan through Extended Events and looked at it. And if you want me to post the code and steps for doing that, I'm happy to, just let me know.

But, if you trust that I'm telling the truth :) then in the output from the query above, for the IX_SalesOrderHeaderEnlarged_SalesPersonID nonclustered index on the [Sales].[SalesOrderHeaderEnlarged] table there are 2158 pages.

For the IX_SalesOrderDetailEnlarged_ProductID index on the [Sales].[SalesOrderDetailEnlarged] table there are 16703 pages. The reads for the check on the foreign key constraint were 19242. That's a little more than 16073 + 2158 (18861), but, here's what's important to note… If you look at the second screen shot you see multiple rows for the check on the foreign key. There's one that has 35 reads and one with 19207 reads. If you look at the statement column you see that the row with 35 reads is for creating a temp table, and 19207 is for inserting into that temp table. So we're getting some additional overhead because a temp table is used to look for invalid data. But, back to your original question…the reads are 100% of the page, plus a bit of overhead. And just for fun, here's the full INSERT statement:

INSERT INTO #priv_cc_temp_table20204

SELECT DISTINCT TOP 200 'Table Name' = '[Sales].[SalesOrderDetailEnlarged]',

CASE

WHEN ( t_1.[SalesOrderID] IS NOT NULL AND t_2.[SalesOrderID] IS NULL )

THEN '[FK_SalesOrderDetailEnlarged_SalesOrderHeaderEnlarged_SalesOrderID]'

END 'Constraint',

CASE

WHEN ( t_1.[SalesOrderID] IS NOT NULL AND t_2.[SalesOrderID] IS NULL )

THEN ( '[SalesOrderID] = "' + REPLACE(CONVERT(NVARCHAR(MAX), t_1.[SalesOrderID], 0),"",""") + "" )

END 'RID' FROM [Sales].[SalesOrderDetailEnlarged] t_1

LEFT JOIN [Sales].[SalesOrderHeaderEnlarged] t_2 ON t_1.[SalesOrderID] = t_2.[SalesOrderID]

WHERE ( ( t_1.[SalesOrderID] IS NOT NULL AND t_2.[SalesOrderID] IS NULL ) )

The execution plan (pulled via Extended Events) is an index scan against both the nonclustereds with a hash match.

Let me know if that all makes sense and if I answered your question.

Now, for your other question – can I compare that in time/resources to work done by CHECKDB? Well, I thought I could…I started the same XEvents session, ran CHECKDB, pulled the info from ring_buffer into a temp table, and then tried to aggregate it. But it didn't show any reads…and I cannot figure out what's going on (I need to with check with Jon), but if I look at the .xel file that I happened to capture I get 185188 reads.

So, CHECKDB is higher than CHECKCONSTRAINTS, which doesn't surprise me. While CHECKDB is efficient in terms of read-ahead, there is still random I/O and tempdb usage…hence the higher value.

E

I forgot clean up code in the post…

DROP TABLE #EventData;

GO

DROP EVENT SESSION [Constraint_Performance] ON SERVER;

GO

Recently, I had rebuilt a table with REPAIR_ALLOW_DATA_LOSS and after that I ran DBCC Checkdb and didn't get any consistency error. After running DBCC checkdb successfully, Do i really need to run DBCC CHECKCONSTRAINT?

Thanks!

Hi-

Yes, even if CHECKDB comes back without errors, if you've run a repair, you still need to run CHECKCONSTRAINTS. CHECKDB does not include the same code that's in CHECKCONSTRAINTS,

Erin