Delayed Durability is a late-breaking but interesting feature in SQL Server 2014; the high-level elevator pitch of the feature is, quite simply:

- "Trade durability for performance."

Some background first. By default, SQL Server uses a write-ahead log (WAL), which means that changes are written to the log before they are allowed to be committed. In systems where transaction log writes become the bottleneck, and where there is a moderate tolerance for data loss, you now have the option to temporarily suspend the requirement to wait for the log flush and acknowledgement. This happens to quite literally take the D out of ACID, at least for a small portion of data (more on this later).

You kind of already make this sacrifice now. In full recovery mode, there is always some risk of data loss, it's just measured in terms of time rather than size. For example, if you back up the transaction log every five minutes, you could lose up to just under 5 minutes of data if something catastrophic happened. I'm not talking simple failover here, but let's say the server literally catches on fire or someone trips over the power cord – the database may very well be unrecoverable and you may have to go back to the point in time of the last log backup. And that's assuming you are even testing your backups by restoring them somewhere – in the event of a critical failure you may not have the recovery point you think you have. We tend not to think about this scenario, of course, because we never expect bad things™ to happen.

How it works

Delayed durability enables write transactions to continue running as if the log had been flushed to disk; in reality, the writes to disk have been grouped and deferred, to be handled in the background. The transaction is optimistic; it assumes that the log flush will happen. The system uses a 60KB chunk of log buffer, and attempts to flush the log to disk when this 60KB block is full (at the latest – it can and often will happen before that). You can set this option at the database level, at the individual transaction level, or – in the case of natively compiled procedures in In-Memory OLTP – at the procedure level. The database setting wins in the case of a conflict; for example, if the database is set to disabled, trying to commit a transaction using the delayed option will simply be ignored, with no error message. Also, some transactions are always fully durable, regardless of database settings or commit settings; for example, system transactions, cross-database transactions, and operations involving FileTable, Change Tracking, Change Data Capture, and Replication.

At the database level, you can use:

ALTER DATABASE dbname SET DELAYED_DURABILITY = DISABLED | ALLOWED | FORCED;

If you set it to ALLOWED, this means that any individual transaction can use Delayed Durability; FORCED means that all transactions that can use Delayed Durability will (the exceptions above are still relevant in this case). You will likely want to use ALLOWED rather than FORCED – but the latter can be useful in the case of an existing application where you want to use this option throughout and also minimize the amount of code that has to be touched. An important thing to note about ALLOWED is that fully durable transactions may have to wait longer, as they will force the flush of any delayed durable transactions first.

At the transaction level, you can say:

COMMIT TRANSACTION WITH (DELAYED_DURABILITY = ON);

And in an In-Memory OLTP natively-compiled procedure, you can add the following option to the BEGIN ATOMIC block:

BEGIN ATOMIC WITH (DELAYED_DURABILITY = ON, ...)

A common question is around what happens with locking and isolation semantics. Nothing changes, really. Locking and blocking still happen, and transactions are committed in the same way and with the same rules. The only difference is that, by allowing the commit to occur without waiting for the log to flush to disk, any related locks are released that much sooner.

When You Should Use It

In addition to the benefit you get from allowing the transactions to proceed without waiting for the log write to happen, you also get fewer log writes of larger sizes. This can work out very well if your system has a high proportion of transactions that are actually smaller than 60KB, and particularly when the log disk is slow (though I found similar benefits on SSD and traditional HDD). It doesn't work out so well if your transactions are, for the most part, larger than 60KB, if they are typically long-running, or if you have high throughput and high concurrency. What can happen here is that you can fill the entire log buffer before the flush finishes, which just means transferring your waits to a different resource and, ultimately, not improving the perceived performance by the users of the application.

In other words, if your transaction log is not currently a bottleneck, don't turn this feature on. How can you tell if your transaction log is currently a bottleneck? The first indicator would be high WRITELOG waits, particularly when coupled with PAGEIOLATCH_**. Paul Randal (@PaulRandal) has a great four-part series on identifying transaction log problems, as well as configuring for optimal performance:

- Trimming the Transaction Log Fat

- Trimming More Transaction Log Fat

- Transaction Log Configuration Issues

- Transaction Log Monitoring

Also see this blog post from Kimberly Tripp (@KimberlyLTripp), 8 Steps to Better Transaction Log Throughput, and the SQL CAT team's blog post, Diagnosing Transaction Log Performance Issues and Limits of the Log Manager.

This investigation may lead you to the conclusion that Delayed Durability is worth looking into; it may not. Testing your workload will be the most reliable way to know for sure. Like many other additions in recent versions of SQL Server (*cough* Hekaton), this feature is NOT designed to improve every single workload – and as noted above, it can actually make some workloads worse. See this blog post by Simon Harvey for some other questions you should ask yourself about your workload to determine if it is feasible to sacrifice some durability to achieve better performance.

Potential for data loss

I'm going to mention this several times, and add emphasis every time I do: You need to be tolerant to data loss. Under a well-performing disk, the maximum you should expect to lose in a catastrophe – or even a planned and graceful shutdown – is up to one full block (60KB). However, in the case where your I/O subsystem can't keep up, it is possible that you could lose as much as the entire log buffer (~7MB).

To clarify, from the documentation (emphasis mine):

So it is very important that you weigh your data loss risk with your need to alleviate transaction log performance issues. If you run a bank or anything dealing with money, it may be much safer and more appropriate for you to move your log to faster disk than to roll the dice using this feature. If you are trying to improve the response time in your Web Gamerz Chat Room application, maybe the risk is less severe.

You can control this behavior to some degree in order to minimize your risk of data loss. You can force all delayed durable transactions to be flushed to disk in one of two ways:

- Commit any fully durable transaction.

- Call

sys.sp_flush_logmanually.

This allows you to revert to controlling data loss in terms of time, rather than size; you could schedule the flush every 5 seconds, for example. But you will want to find your sweet spot here; flushing too often can offset the Delayed Durability benefit in the first place. In any case, you will still need to be tolerant to data loss, even if it is only <n> seconds' worth.

You would think that CHECKPOINT might help here, but this operation actually does not technically guarantee the log will be flushed to disk.

Interaction with HA/DR

You might wonder how Delayed Durablity functions with HA/DR features such as log shipping, replication, and Availability Groups. With most of these it works unchanged. Log shipping and replication will replay the log records that have been hardened, so the same potential for data loss exists there. With AGs in asynchronous mode, we're not waiting for the secondary acknowledge anyway, so it will behave the same as today. With synchronous, however, we can't commit on the primary until the transaction is committed and hardened to the remote log. Even in that scenario we may have some benefit locally by not having to wait for the local log to write, we still have to wait for the remote activity. So in that scenario there is less benefit, and potentially none; except perhaps in the rare scenario where the primary's log disk is really slow and the secondary's log disk is really fast. I suspect the same conditions hold true for sync/async mirroring, but you won't get any official commitment from me about how a shiny new feature works with a deprecated one. :-)

Performance Observations

This wouldn't be much of a post here if I didn't show some actual performance observations. I set up 8 databases to test the effects of two different workload patterns with the following attributes:

- Recovery model: simple vs. full

- Log location: SSD vs. HDD

- Durability: delayed vs. fully durable

I am really, really, really lazyefficient about this kind of thing. Since I want to avoid repeating the same operations within each database, I created the following table temporarily in model:

USE model;

GO

CREATE TABLE dbo.TheTable

(

TheID INT IDENTITY(1,1) PRIMARY KEY,

TheDate DATETIME NOT NULL DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP,

RowGuid UNIQUEIDENTIFIER NOT NULL DEFAULT NEWID()

);

Then I built a set of dynamic SQL command to builds these 8 databases, rather than create the databases individually and then muck with the settings:

-- C and D are SSD, G is HDD

DECLARE @sql NVARCHAR(MAX) = N'';

;WITH l AS (SELECT l FROM (VALUES('D'),('G')) AS l(l)),

r AS (SELECT r FROM (VALUES('FULL'),('SIMPLE')) AS r(r)),

d AS (SELECT d FROM (VALUES('FORCED'),('DISABLED')) AS d(d)),

x AS (SELECT l.l, r.r, d.d, n = CONVERT(CHAR(1),ROW_NUMBER() OVER

(ORDER BY d.d DESC, l.l)) FROM l CROSS JOIN r CROSS JOIN d)

SELECT @sql += N'

CREATE DATABASE dd' + n + ' ON '

+ '(name = ''dd' + n + '_data'','

+ ' filename = ''C:\SQLData\dd' + n + '.mdf'', size = 1024MB)

LOG ON (name = ''dd' + n + '_log'','

+ ' filename = ''' + l + ':\SQLLog\dd' + n + '.ldf'', size = 1024MB);

ALTER DATABASE dd' + n + ' SET RECOVERY ' + r + ';

ALTER DATABASE dd' + n + ' SET DELAYED_DURABILITY = ' + d + ';'

FROM x ORDER BY d, l;

PRINT @sql;

-- EXEC sp_executesql @sql;

Feel free to run this code yourself (with the EXEC still commented out) to see that this would create 4 databases with Delayed Durability OFF (two in FULL recovery, two in SIMPLE, one of each with log on slow disk, and one of each with log on SSD). Repeat that pattern for 4 databases with Delayed Durability FORCED – I did this to simplify the code in the test, rather than to reflect what I would do in real life (where I would likely want to treat some transactions as critical, and some as, well, less than critical).

For sanity checking, I ran the following query to ensure that the databases had the right matrix of attributes:

SELECT d.name, d.recovery_model_desc, d.delayed_durability_desc,

log_disk = CASE WHEN mf.physical_name LIKE N'D%' THEN 'SSD' else 'HDD' END

FROM sys.databases AS d

INNER JOIN sys.master_files AS mf

ON d.database_id = mf.database_id

WHERE d.name LIKE N'dd[1-8]'

AND mf.[type] = 1; -- log

Results:

| name | recovery_model | delayed_durability | log_disk |

|---|---|---|---|

| dd1 | FULL | FORCED | SSD |

| dd2 | SIMPLE | FORCED | SSD |

| dd3 | FULL | FORCED | HDD |

| dd4 | SIMPLE | FORCED | HDD |

| dd5 | FULL | DISABLED | SSD |

| dd6 | SIMPLE | DISABLED | SSD |

| dd7 | FULL | DISABLED | HDD |

| dd8 | SIMPLE | DISABLED | HDD |

Relevant configuration of the 8 test databases

I also ran the test cleanly multiple times to ensure that a 1 GB data file and 1 GB log file would be sufficient to run the entire set of workloads without introducing any autogrowth events into the equation. As a best practice, I routinely go out of my way to ensure customers' systems have enough allocated space (and proper alerts built in) such that no growth event ever occurs at an unexpected time. In the real world I know this doesn't always happen, but it is ideal.

I set up the system to be monitored with SQL Sentry – this would allow me to easily show most of the performance metrics I wanted to highlight. But I also created a temporary table to store batch metrics including duration and very specific output from sys.dm_io_virtual_file_stats:

SELECT test = 1, cycle = 1, start_time = GETDATE(), *

INTO #Metrics

FROM sys.dm_io_virtual_file_stats(DB_ID('dd1'), 2) WHERE 1 = 0;

This would allow me to record the start and finish time of each individual batch, and measure deltas in the DMV between start time and end time (only reliable in this case because I know I'm the only user on the system).

Lots of small transactions

The first test I wanted to perform was a lot of small transactions. For each database, I wanted to end up with 500,000 separate batches of a single insert each:

INSERT #Metrics SELECT 1, 1, GETDATE(), *

FROM sys.dm_io_virtual_file_stats(DB_ID('dd1'), 2);

GO

INSERT dbo.TheTable DEFAULT VALUES;

GO 500000

INSERT #Metrics SELECT 1, 2, GETDATE(), *

FROM sys.dm_io_virtual_file_stats(DB_ID('dd1'), 2);

Remember, I try to be lazyefficient about this kind of thing. So to generate the code for all 8 databases, I ran this:

;WITH x AS

(

SELECT TOP (8) number FROM master..spt_values

WHERE type = N'P' ORDER BY number

)

SELECT CONVERT(NVARCHAR(MAX), N'') + N'

INSERT #Metrics SELECT 1, 1, GETDATE(), *

FROM sys.dm_io_virtual_file_stats(DB_ID(''dd' + RTRIM(number+1) + '''), 2);

GO

INSERT dbo.TheTable DEFAULT VALUES;

GO 500000

INSERT #Metrics SELECT 1, 2, GETDATE(), *

FROM sys.dm_io_virtual_file_stats(DB_ID(''dd' + RTRIM(number+1) + '''), 2);'

FROM x;

I ran this test and then looked at the #Metrics table with the following query:

SELECT

[database] = db_name(m1.database_id),

num_writes = m2.num_of_writes - m1.num_of_writes,

write_bytes = m2.num_of_bytes_written - m1.num_of_bytes_written,

bytes_per_write = (m2.num_of_bytes_written - m1.num_of_bytes_written)*1.0

/(m2.num_of_writes - m1.num_of_writes),

io_stall_ms = m2.io_stall_write_ms - m1.io_stall_write_ms,

m1.start_time,

end_time = m2.start_time,

duration = DATEDIFF(SECOND, m1.start_time, m2.start_time)

FROM #Metrics AS m1

INNER JOIN #Metrics AS m2

ON m1.database_id = m2.database_id

WHERE m1.cycle = 1 AND m2.cycle = 2

AND m1.test = 1 AND m2.test = 1;

This yielded the following results (and I confirmed through multiple tests that the results were consistent):

| database | writes | bytes | bytes/write | io_stall_ms | start_time | end_time | duration (seconds) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dd1 | 8,068 | 261,894,656 | 32,460.91 | 6,232 | 2014-04-26 17:20:00 | 2014-04-26 17:21:08 | 68 |

| dd2 | 8,072 | 261,682,688 | 32,418.56 | 2,740 | 2014-04-26 17:21:08 | 2014-04-26 17:22:16 | 68 |

| dd3 | 8,246 | 262,254,592 | 31,803.85 | 3,996 | 2014-04-26 17:22:16 | 2014-04-26 17:23:24 | 68 |

| dd4 | 8,055 | 261,688,320 | 32,487.68 | 4,231 | 2014-04-26 17:23:24 | 2014-04-26 17:24:32 | 68 |

| dd5 | 500,012 | 526,448,640 | 1,052.87 | 35,593 | 2014-04-26 17:24:32 | 2014-04-26 17:26:32 | 120 |

| dd6 | 500,014 | 525,870,080 | 1,051.71 | 35,435 | 2014-04-26 17:26:32 | 2014-04-26 17:28:31 | 119 |

| dd7 | 500,015 | 526,120,448 | 1,052.20 | 50,857 | 2014-04-26 17:28:31 | 2014-04-26 17:30:45 | 134 |

| dd8 | 500,017 | 525,886,976 | 1,051.73 | 49,680 | 133 |

Small transactions: Duration and results from sys.dm_io_virtual_file_stats

Definitely some interesting observations here:

- Number of individual write operations was very small for the Delayed Durability databases (~60X for traditional).

- Total number of bytes written was cut in half using Delayed Durability (I presume because all of the writes in the traditional case contained a lot of wasted space).

- The number of bytes per write was a lot higher for Delayed Durability. This was not overly surprising, since the whole purpose of the feature is to bundle writes together in larger batches.

- The total duration of I/O stalls was volatile, but roughly an order of magnitude lower for Delayed Durability. The stalls under fully durable transactions were much more sensitive to the type of disk.

- If anything hasn't convinced you so far, the duration column is very telling. Fully durable batches that take two minutes or more are cut almost in half.

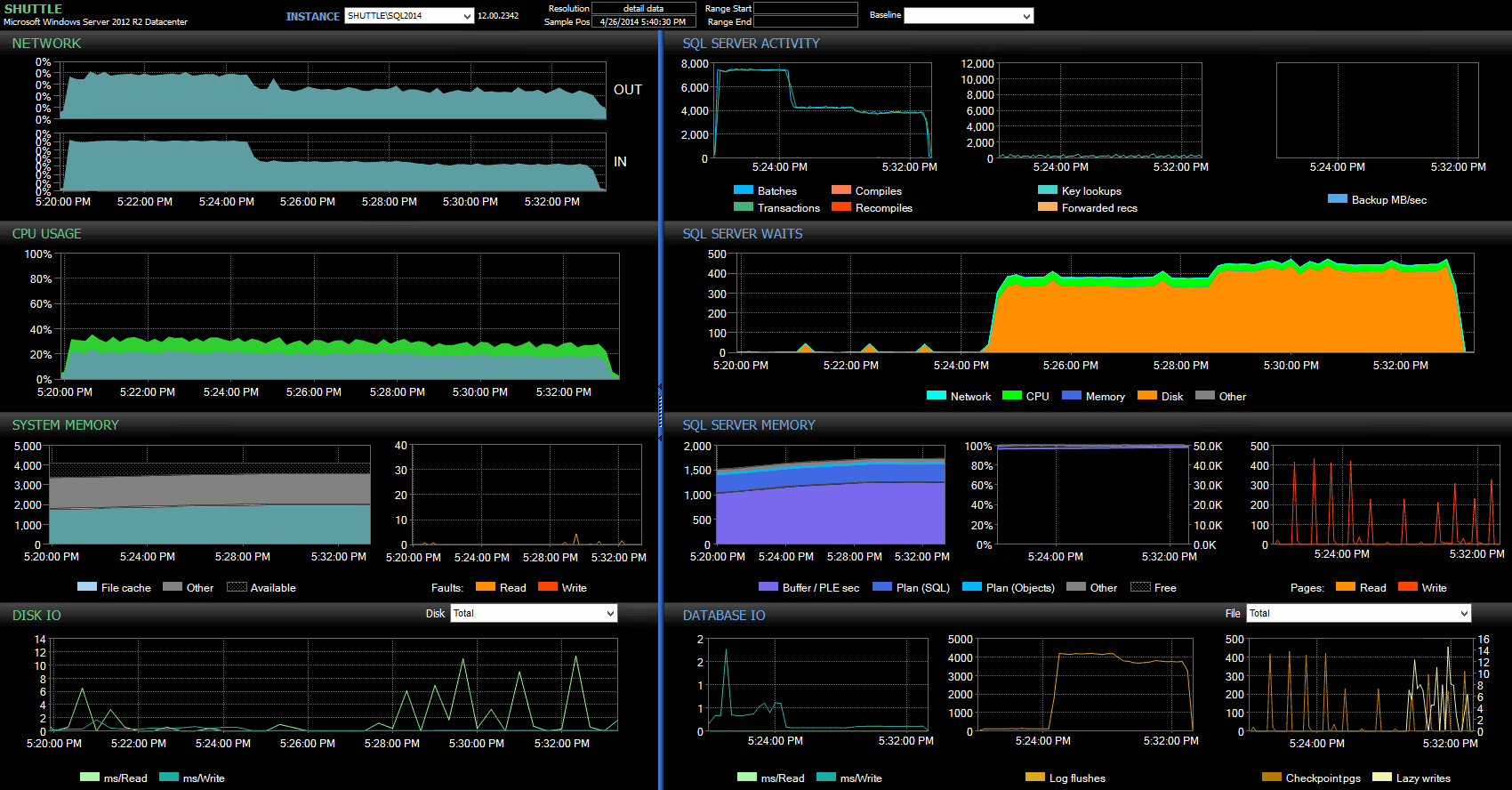

The start/end time columns allowed me to focus on the Performance Advisor dashboard for the precise period where these transactions were happening, where we can draw a lot of additional visual indicators:

SQL Sentry dashboard – click to enlarge

Further observations here:

- On several graphs, you can clearly see exactly when the non-Delayed Durability portion of the batch took over (~5:24:32 PM).

- There is no observable impact to CPU or memory when using Delayed Durability.

- You can see a tremendous impact to batches/transactions per second in the first graph under SQL Server Activity.

- SQL Server waits go through the roof when the fully durable transactions started. These were comprised almost exclusively of

WRITELOGwaits, with a small number ofPAGEIOLOATCH_EXandPAGEIOLATCH_UPwaits for good measure. - The total number of log flushes throughout the Delayed Durability operations was quite small (low 100s/sec), while this jumped to over 4,000/sec for the traditional behavior (and slightly lower for the HDD duration of the test).

Fewer, larger transactions

For the next test, I wanted to see what would happen if we performed fewer operations, but made sure each statement affected a larger amount of data. I wanted this batch to run against each database:

CREATE TABLE dbo.Rnd

(

batch TINYINT,

TheID INT

);

INSERT dbo.Rnd SELECT TOP (1000) 1, TheID FROM dbo.TheTable ORDER BY NEWID();

INSERT dbo.Rnd SELECT TOP (10) 2, TheID FROM dbo.TheTable ORDER BY NEWID();

INSERT dbo.Rnd SELECT TOP (300) 3, TheID FROM dbo.TheTable ORDER BY NEWID();

GO

INSERT #Metrics SELECT 1, GETDATE(), *

FROM sys.dm_io_virtual_file_stats(DB_ID('dd1'), 2);

GO

UPDATE t SET TheDate = DATEADD(MINUTE, 1, TheDate)

FROM dbo.TheTable AS t

INNER JOIN dbo.Rnd AS r

ON t.TheID = r.TheID

WHERE r.batch = 1;

GO 10000

UPDATE t SET RowGuid = NEWID()

FROM dbo.TheTable AS t

INNER JOIN dbo.Rnd AS r

ON t.TheID = r.TheID

WHERE r.batch = 2;

GO 10000

DELETE dbo.TheTable WHERE TheID IN (SELECT TheID FROM dbo.Rnd WHERE batch = 3);

DELETE dbo.TheTable WHERE TheID IN (SELECT TheID+1 FROM dbo.Rnd WHERE batch = 3);

DELETE dbo.TheTable WHERE TheID IN (SELECT TheID-1 FROM dbo.Rnd WHERE batch = 3);

GO

INSERT #Metrics SELECT 2, GETDATE(), *

FROM sys.dm_io_virtual_file_stats(DB_ID('dd1'), 2);

So again I used the lazy method to produce 8 copies of this script, one per database:

;WITH x AS (SELECT TOP (8) number FROM master..spt_values WHERE type = N'P' ORDER BY number)

SELECT N'

USE dd' + RTRIM(Number+1) + ';

GO

CREATE TABLE dbo.Rnd

(

batch TINYINT,

TheID INT

);

INSERT dbo.Rnd SELECT TOP (1000) 1, TheID FROM dbo.TheTable ORDER BY NEWID();

INSERT dbo.Rnd SELECT TOP (10) 2, TheID FROM dbo.TheTable ORDER BY NEWID();

INSERT dbo.Rnd SELECT TOP (300) 3, TheID FROM dbo.TheTable ORDER BY NEWID();

GO

INSERT #Metrics SELECT 2, 1, GETDATE(), *

FROM sys.dm_io_virtual_file_stats(DB_ID(''dd' + RTRIM(number+1) + ''', 2);

GO

UPDATE t SET TheDate = DATEADD(MINUTE, 1, TheDate)

FROM dbo.TheTable AS t

INNER JOIN dbo.rnd AS r

ON t.TheID = r.TheID

WHERE r.cycle = 1;

GO 10000

UPDATE t SET RowGuid = NEWID()

FROM dbo.TheTable AS t

INNER JOIN dbo.rnd AS r

ON t.TheID = r.TheID

WHERE r.cycle = 2;

GO 10000

DELETE dbo.TheTable WHERE TheID IN (SELECT TheID FROM dbo.rnd WHERE cycle = 3);

DELETE dbo.TheTable WHERE TheID IN (SELECT TheID+1 FROM dbo.rnd WHERE cycle = 3);

DELETE dbo.TheTable WHERE TheID IN (SELECT TheID-1 FROM dbo.rnd WHERE cycle = 3);

GO

INSERT #Metrics SELECT 2, 2, GETDATE(), *

FROM sys.dm_io_virtual_file_stats(DB_ID(''dd' + RTRIM(number+1) + '''), 2);'

FROM x;

I ran this batch, then changed the query against #Metrics above to look at the second test instead of the first. The results:

| database | writes | bytes | bytes/write | io_stall_ms | start_time | end_time | duration (seconds) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dd1 | 20,970 | 1,271,911,936 | 60,653.88 | 12,577 | 2014-04-26 17:41:21 | 2014-04-26 17:43:46 | 145 |

| dd2 | 20,997 | 1,272,145,408 | 60,587.00 | 14,698 | 2014-04-26 17:43:46 | 2014-04-26 17:46:11 | 145 |

| dd3 | 20,973 | 1,272,982,016 | 60,696.22 | 12,085 | 2014-04-26 17:46:11 | 2014-04-26 17:48:33 | 142 |

| dd4 | 20,958 | 1,272,064,512 | 60,695.89 | 11,795 | 143 | ||

| dd5 | 30,138 | 1,282,231,808 | 42,545.35 | 7,402 | 2014-04-26 17:50:56 | 2014-04-26 17:53:23 | 147 |

| dd6 | 30,138 | 1,282,260,992 | 42,546.31 | 7,806 | 2014-04-26 17:53:23 | 2014-04-26 17:55:53 | 150 |

| dd7 | 30,129 | 1,281,575,424 | 42,536.27 | 9,888 | 2014-04-26 17:55:53 | 2014-04-26 17:58:25 | 152 |

| dd8 | 30,130 | 1,281,449,472 | 42,530.68 | 11,452 | 2014-04-26 17:58:25 | 2014-04-26 18:00:55 | 150 |

Larger transactions: Duration and results from sys.dm_io_virtual_file_stats

This time, the impact of Delayed Durability is much less noticeable. We see a slightly smaller number of write operations, at a slightly larger number of bytes per write, with the total bytes written almost identical. In this case we actually see the I/O stalls are higher for Delayed Durability, and this likely accounts for the fact that the durations were almost identical as well.

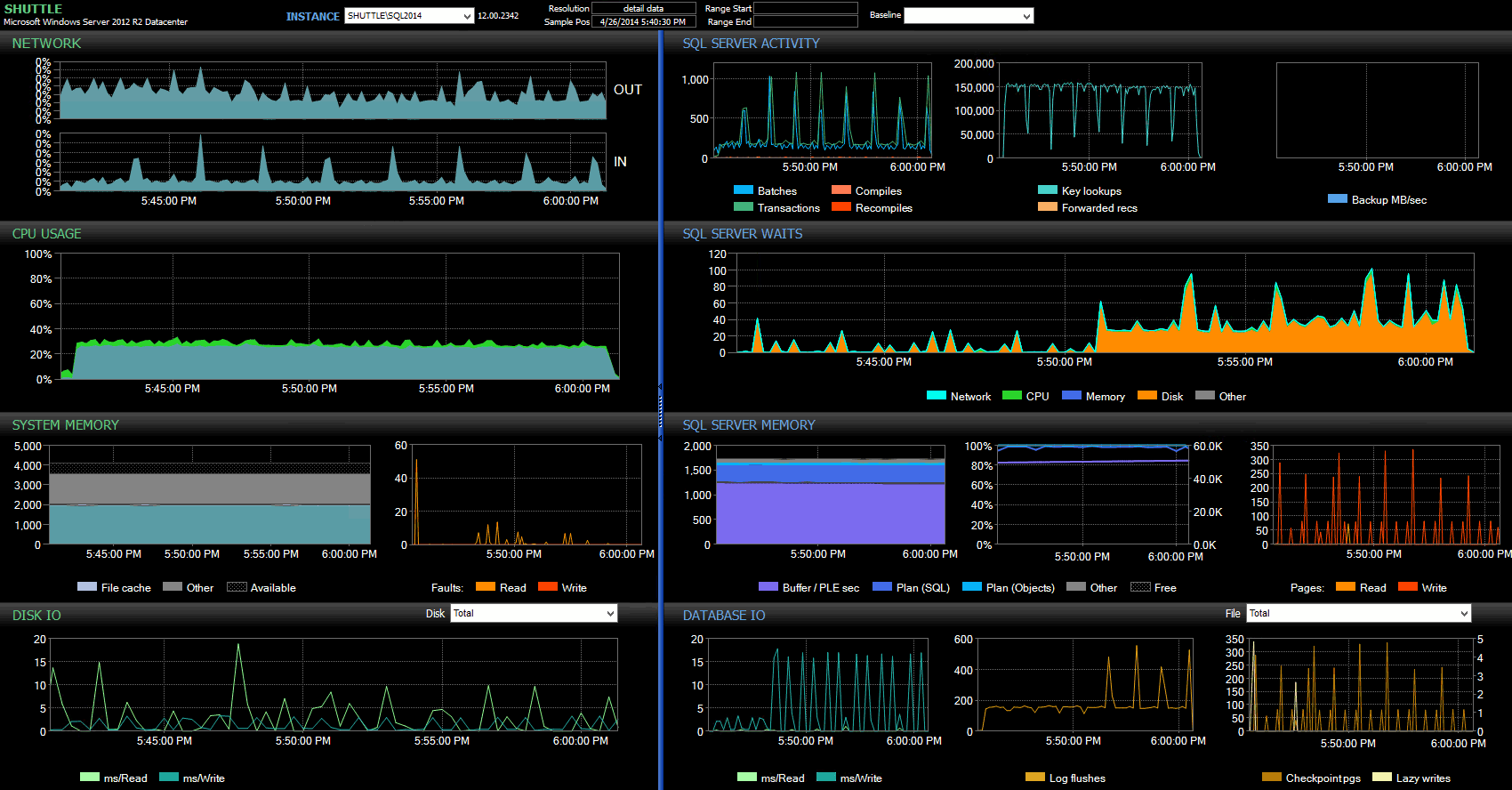

From the Performance Advisor dashboard, we some similarities with the previous test, and some stark differences as well:

SQL Sentry dashboard – click to enlarge

One of the big differences to point out here is that the delta in wait stats is not quite as pronounced as with the previous test – there is still a much higher frequency of WRITELOG waits for the fully durable batches, but nowhere near the levels seen with the smaller transactions. Another thing you can spot immediately is that the previously observed impact on batches and transactions per second is no longer present. And finally, while there are more log flushes with fully durable transactions than when delayed, this disparity is far less pronounced than with the smaller transactions.

Conclusion

It should be clear that there are certain workload types that may benefit greatly from Delayed Durability – provided, of course, that you have a tolerance for data loss. This feature is not restricted to In-Memory OLTP, is available on all editions of SQL Server 2014, and can be implemented with little to no code changes. It can certainly be a powerful technique if your workload can support it. But again, you will need to test your workload to be sure that it will benefit from this feature, and also strongly consider whether this increases your exposure to the risk of data loss.

As an aside, this may seem to the SQL Server crowd like a fresh new idea, but in truth Oracle introduced this as "Asynchronous Commit" in 2006 (see COMMIT WRITE ... NOWAIT as documented here and blogged about in 2007). And the idea itself has been around for nearly 3 decades; see Hal Berenson's brief chronicle of its history.

Next Time

One idea that I have batted around is to try to improve the performance of tempdb by forcing Delayed Durability there. One special property of tempdb that makes it such a tempting candidate is that it is transient by nature – anything in tempdb is designed, explicitly, to be tossable in the wake of a wide variety of system events. I am saying this now without having any idea if there is a workload shape where this will work out well; but I do plan to try it out, and if I find anything interesting, you can be sure I will post about it here.

Really nice write up Aaron. The tempdb angle has really piqued my curiosity.

Very nicely written. Thanks.

Thanks for the great article, Aaron. Under the section 'Potential for data loss' it mentions that you could lose up to 7MB, the size of the entire log buffers. I understand that each log buffer is 60KB so that works out as about 120 individual log buffers making up the entire set of log buffers (the object that's referred to the log cache I guess). Is there any Microsoft article (MSDN or CSS) that mentions that the total number of log buffers totals to 7MB ?

Also, I was under the impression that as soon as a 60KB log buffer is full it is written to disk so I was thinking that the maximum data loss would be 60KB. But I'm guessing the maximum data loss scenario you're referring to is when all 120 individual log buffers are not completely full so they're not flushed to disk and it's then that the SQL Server goes down. Just wondering if I'm correctly outlining this scenario.

Thanks again.

@LondonDBA you are right, the ~7MB refers to 120 log buffer blocks at just under 60kb each, assuming that the worst case scenario would be a really slow I/O subsystem and the lucky coincidence of having 59kb or so in every single log buffer block at the time disaster struck. This is a lot like winning the lottery, and I doubt the data loss would ever be even close to that severe, but it can't be guaranteed to be any better. I don't know that the 7MB figure is called out in any explicit documentation on MSDN, but I do believe I saw it referenced on a slide deck at TechEd or the PASS Community Summit. I don't think they will officially document it at this time because the potential for data loss could change (at any point – under a trace flag, via a CU, etc. they could change the number of log blocks in the buffer or the size of the blocks themselves).

The 7MB is referenced in the SQLPASS 2013 Summit session 'DBA-406-M SQL Server Transaction Log Internals' presented by Tim Chapman and Denzil Ribeiro so that might have been where you saw it Aaron.

Thanks Mark, I think you're right!

Hi Aaron

I did some testing to reproduce data loss with delayed durability. I

1. Took a test system with 4 CPUs and 64 GB RAM. Actually, it was a dev system just handed over for deployment, which I decided to use for little testing. Installed SQL 2014(ver 12.0.2402) on it.

2. Created a database with just one table in it that has one column of char(2). Enabled "Forced" Delayed Durability on the database.

3. Created a script file for DISKPART to take log and data drives offline.

4. Created statement to insert only one record with "(DELAYED_DURABILITY = ON)" within the transaction.

5. Created statement to run Diskpart using XP_CMDSHELL

6. Created statement to kill(taskkill) SQL process using XP_CMDSHELL

7. Selected the transaction for insert and the statements in step 5 and 6 and executed them in on go. This inserted one record in the table with delayed durability, took the log and data drives offline, and killed SQL process.

8. Brought the disks online after confirming that SQL was down

9. Brought SQL online and checked records in the table.

To my surprise, the table shows the new record that should have been lost. I have tested this scenario many times with same result.

There is nothing else running on this test box. SQL agent is stopped throughout the test. After restart, I have verified that the ;pg record fixed length and log record length are not large enough to fill the log buffer(60KB).

Any ideas on why the transaction is always making it into the log file?

I think there is a misunderstanding – the claim is that data loss is *possible*, not that it is likely, never mind *guaranteed.* I'd say the feature is working better than you should have expected. :-)

Now, try making sure that your insert transaction exceeds 60kb (or 8MB if you want to have some real fun).

Thanks Aaron for your reply!

It appears that SQL tries to flush log as soon as it can without waiting for 60KB log block to get full even in case of delayed durable transactions just like it does in case of durable transactions. The only thing that has happened with delayed durability is decoupling of transaction commit from log flush.

I have read on several blogs about SQL flushing log only after 60KB log block is full unless a fully durable transaction comes in or someone runs log flush command manually. This statement does not appear to be accurate.

Please let me know if I am mistaken.

I must not have read any of the articles you're talking about, because I don't recall anyone claiming that SQL Server will sit around and wait until a 60kb log block is full before writing. The disclaimer is that you *could* lose that much data if a perfect storm happens – you've committed some data and lightning strikes before SQL Server has had a chance to write to disk. This could happen regardless of whether you've committed 1kb, 30kb, or 59kb. It could be even more than one log block depending on your I/O subsystem. That doesn't mean it is easy to reproduce that scenario – you just need to keep in mind that it is possible.

Hey Aaron,

I love this article and keep coming back to reference it. I just noticed your last paragraph about tempdb, and I was wondering about it myself. I tried changing the setting and saw _no_ improvement in performance. Take a look at this short but very interesting post from a SQL Server development team member that explains why: http://blogs.msdn.com/b/ialonso/archive/2014/07/23/applying-delayed-durability-forced-on-tempdb.aspx . It turns out that even though you cannot apply Delayed Durability on tempdb, the way it flushes the log cache is already very similar to the DD setting. Apparently, it has been this way for a while now.

Great article Aaron.

Really appreciate some of the detail you went into on what is actually being logged with DD on and off. Should give people some good insight into when and why DD might make a difference

Thanks Simon, my colleague Melissa Connors also wrote a post on DD recently that you might find interesting:

Hi Aaron,

Great article, very informative, 1 point to add, Delayed Durability is not supported with Transactional Replication, Microsoft Docs:

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/sql/relational-databases/logs/control-transaction-durability

I have tested myself, if it is enabled on a replicated database, good bye to replication, it will give the famous error: "The row was not found on the subscriber", then you will have to generate a new Snapshot to overcome this issue. Sad.

Regards,

Hany Helmy

Yes already mentioned by Aaron as CDC is fully durable. FYI, CDC uses log reader the same in transaction replication.

Did you ever try this on TempDB?

The new COMPRESS() function is great but is rather slow.

Does anyone know if delayed durability on an INSERT with a COMPRESS() function means that the COMPRESS() itself does not need to complete before the INSERT is considered "complete" and control is sent back to the caller / the code doing the "INSERT"?

@Manish, CDC is not considered as replication at all even if it uses log reader the same in transaction replication. I was talking about replication technology only.

Great article – on conducting some tests we can see the improvement DD has on writes to our Process_Log table that happens when a certain step is processed in an SP. However to officially implement this i could with help around its ability to work within the full structure of our system

let me try an explain it :

We have an SP (SP#1) that executes another SP (SP#2) called "activity_log.sql" at each important step

SP#1 has a step called 'Write client data to table' within a transaction

SP #2 is called at this step and this writes the step details into the Activity_Log table recording a success of fail within another transaction

The transaction is SP#2 is essentially nested in the transaction in SP#1

The Delayed Durability = 'On' is set within the Commit on the transaction in SP#2

Will this affect any further processing in original SP#1? Will DD remain on for the duration of SP#1 or only during the write to Activity_log table in SP#2?

There are lots of SP#1's so simply moving the DD to SP#1 is not an possibity